DDoS and you

Do you hear horror stories of China attacking services you use or of 4Chan taking out services with their Low Orbit Ion Cannon? After hearing stories like that, do you think, “Wait. What?” or, “How does this even work?” or even, “Why can random people take down other people’s websites?” Then this is the article for you.

I’m here to attempt to explain the world of denial-of-service attacks, and to offer some strategies for survival in this complicated Internet world.

What is a DDoS?

A DDoS is a Distributed Denial-of-Service attack. These attacks are happening constantly on the Internet, wars initiated by humans and played out by computers attacking other computers, hoping to make targeted computers inaccessible or overloaded.

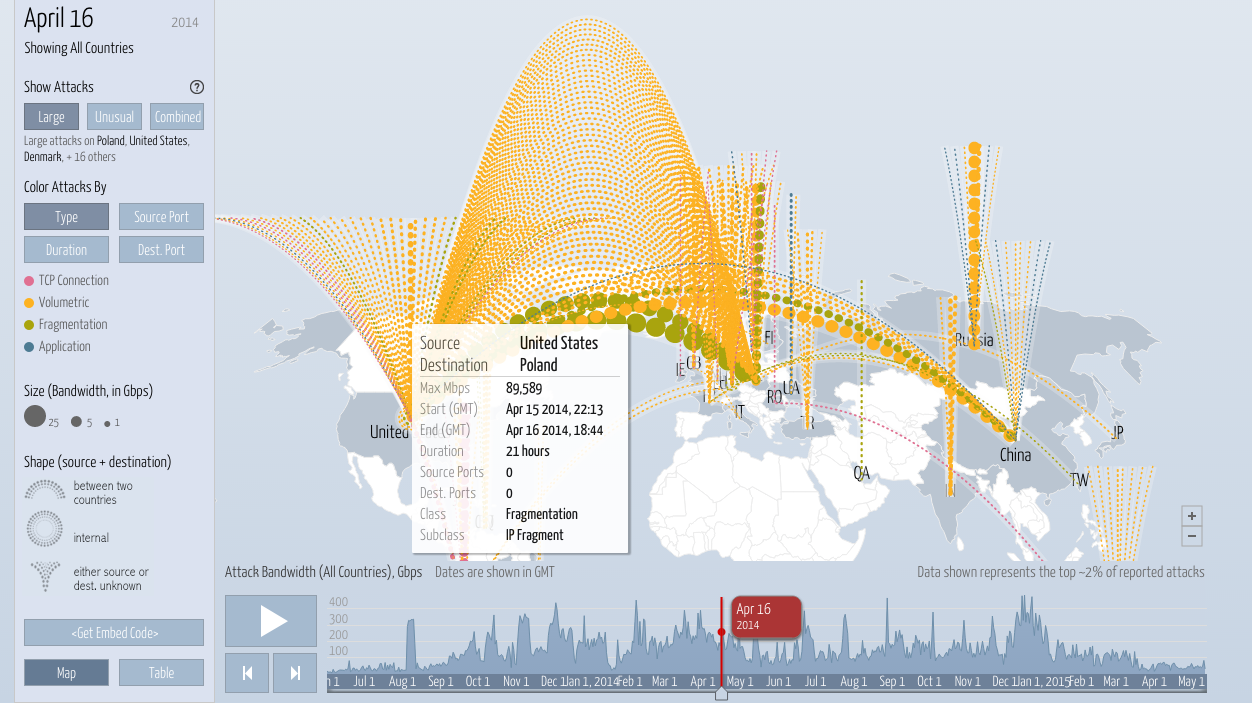

The Digital Attack Map, built collaboratively by Google Ideas and Arbor Networks, displays a snapshot of Internet attack activity at any one time. Particularly interesting is the gallery, which shows a bunch of exciting days on the Internet.

One of my recent favorites is from April 16, 2014, described as, “Volumetric attacks targeting Poland with sustained levels of over 100 Gbps.” I haven’t taken the time to figure out why this attack happened (because often such things don’t make the news, nor does it matter), but it’s interesting to know that so much data is being thrown around. For reference, there are eight gigabits in a gigabyte, so one hundred gigabits per second is twelve and a half gigabytes of data. A 720p Blu-ray movie rip is approximately six and a quarter gigabytes in size (movies are often in the four- to ten-gigabyte range), so someone was pushing two entire movies every second to computers based in Poland.

The Digital Attack Map actually has a fantastic Understanding DDoS page. It includes a few videos on how to use the site, what each part of the site means, and what DDoS is.

The key point is that these attacks can come from any type of network connection. When I talk about defenses, this will be important. But first, let’s talk about the main types of attacks using the names that the Attack Map uses.

-

TCP connection attacks

The Transmission Control Protocol, commonly known as TCP, is the networking protocol of the Internet. It provides reliable, ordered and error-checked delivery of data in the form of packets (unlike UDP). However, TCP connections can be made by attackers to never close, and computers (such as load balancers, HTTP servers, and routers) have a limited number of connections they can keep open. So if someone can take and hold the connections your computer has available to connect to others, others will not be able to connect to you.

-

Volumetric attacks

A volumetric attack (relating to volume, or how much stuff a three-dimensional object can contain) is what it sounds like. Your network connection is like a pipe (joke) that can only transport a certain amount of data at once. Also, your computer can only process a finite amount of data at once. So if someone starts sending lots of bits to your computer, a couple of different things can happen. Either responses will start to slow down as your computer takes more and more time to process the large requests, or the network connection will slow down because the bandwidth between your server and the Internet is diminished by traffic congestion.

-

Fragmentation attacks

Remember how I said TCP “provides reliable, ordered and error-checked delivery of data”? Well, an attacker can purposely send bad data. Some examples are SYN Floods, PING Floods and Teardrop Attacks, among many others. These attacks look different depending on their implementation, but they follow the high-level idea of forcing the target computer to spend an abnormally large amount of time repairing incoming data. A metaphorical example is: Imagine if every time you ordered something on Amazon, instead of getting the actual thing, you got a disassembled Lego kit with no instructions that could possibly be assembled to create the thing you wanted.

-

Application attacks

Application attacks are interesting because they are hard to detect. They look like normal user traffic but target a specific part of an application to bring a server to its knees. For example, imagine a search engine called

example.comthat has a URLhttp://example.com/doalltheworkthat, when visited, performs uncached lookups to the search engine’s database that are very CPU intensive. An attacker finds this and sends thousands of requests to this URL, which causes the servers to use up all of their CPU resources.

Not all of these attacks are necessarily malicious. Some readers may remember the term “Slashdotted,” which referred to a situation when a website was featured on Slashdot and the traffic directed to the site took it offline. We still see this effect from time to time when sites unexpectedly get featured on sites like Hacker News or Reddit.

Where is it all coming from?

Now that you have a rough idea of what DDoS attacks are, the next questions are, “How do attackers get all of this processing power?” and, “Where does it all come from?” These are valid questions. Sadly, the answers to these questions are complicated, because there are many avenues that can provide attackers with large attack pools.

Botnets

Botnets could be a topic all their own, but in a high-level sense, a botnet is a bunch of computers (usually at least ten and sometimes up to hundreds of thousands). Some botnets have done a lot of damage on the Internet. Botnets can be created in many ways, but one of the most common ways is to have a virus infect a computer and then wait for a command. Infected computers connect to an IRC channel or some other control center, and when the person in charge says, “Go!” they start some sort of attack or action. It should be noted that it is illegal in the United States to infect computers without the owner’s consent.

Many of these viruses exploit known security holes, so this is as good a time as any to remind you to update your passwords and keep your computer software patched. Windows users were historically the target of many virus exploits, but these days just about everyone is constantly targeted. I try to make sure all of my computers are up-to-date on the first day of every month, but you can also simply add automation to your system updates on many operating systems (tell your Mac to auto-install security updates, enable automatic apt-get updates, make sure Windows Auto-Updates are enabled, etc.).

To recap, a botnet is a group of compromised computers that listen for commands and then respond by carrying out attacks or actions. Many botnets are created by scanning the Internet for computers that are vulnerable to known exploits and then infecting them with code to make them unknowing members of a botnet.

DNS amplification and IP spoofing

DNS amplification attacks are one way to make it look like you’re being attacked from one location when you’re really being attacked from another. Basically, the attacker sends a request to one or more DNS servers. This request has a false source address, so when the DNS servers respond, they respond to the target instead of to the attacker who originated the request. The target then sees a lot of traffic from the DNS servers but has no idea where the requests originated. Making matters worse, these responses are often quite large in comparison to the initial request, thanks to DNS recursion, which allows someone to ask DNS servers for information that the servers do not know. The servers will query other DNS servers to get that information and then return it. For a 64-byte request, you could get a 3876-byte response, for example.

This type of attack is a form of IP spoofing. Similarly, last year we saw a string of NTP amplification attacks. NTP is the Network Time Protocol and is unauthenticated like DNS. It, too, can receive requests that cause the NTP server to send responses larger than the original request to computers that did not make the initial request. DNS and NTP are just two examples of IP spoofing. There is constant ongoing research by attackers to find new services that are susceptible to these types of attacks.

The US CERT article linked earlier on DNS amplification has a lot of data on these types of attacks, but one key detail is particularly important: In 2000, the IETF proposed Best Current Practice 38. Titled, “Network Ingress Filtering: Defeating Denial of Service Attacks which employ IP Source Address Spoofing,” this proposal suggested that ISPs verify packets on their networks are actually coming from their stated origin (i.e., where they say they are coming from). In 2012 it was suggested that 80% of the Internet does this, which is fairly good news. This relatively high level of adherence to best practices goes a long way toward helping protect you without you having to do anything, but these sorts of attacks still happen, and you should remain aware of them.

Many hosting providers and networks also implement egress filtering. Egress filtering is the opposite of ingress filtering. In egress filtering, routers examine traffic as it leaves the network. Checks are configured on a per network basis, but common checks are to verify that packets leaving the network have an IP belonging to that network and to make sure the traffic type is allowed (such as DNS, HTTP or SMTP). This filtering helps prevent traffic from going across networks that are unrelated to the request.

Why should I care?

Engineering is a never-ending problem of cost-benefit analysis. With no constraints, an engineering team can prepare for a large set of possibilities of failure given enough imagination, time and money. But in reality, every system has different reliability requirements. For example, my personal website does not need to be as reliable as gmail.com, which does not need to be as reliable as a plane’s fly-by-wire system.

Imagine your site is down for an hour. Now a day. Now a week. Will this hurt your livelihood? Will it cost you money? Will people die?

If yes, that’s a good thing to know, and you should be prepared to make investments to counteract bad outcomes. As the Digital Attack Map website mentions, your attackers can buy a lot of sustained attack power for $125.

What protections are available?

Protecting yourself from DDoS is complicated: As we have not created the Minority Report system to predict all of the possible attacks in the world, we have no idea who will become a target, when an attack will occur, or how large an attack will be.

But even if you’re small, don’t have a lot of resources to invest, and have a history of angering people who tend to initiate cyber-attacks against people they disagree with (such as the US Government, the Chinese Government, religious extremists or “hacktivists”), there are still some things you can do to protect yourself.

If you’re a source of free expression that a government or other group is trying to silence, you can apply for Google Ideas’ new Project Shield.

If you are not, you can use one of many for-pay services from large companies that have extra bandwidth and large networks to absorb attacks. Akamai, Amazon, CloudFlare, Google and others all have products like this.

Further reading and research

I mentioned in the introduction that there are strategies for surviving these types of attacks. The last section of this article gave a taste of some of these, but I have only included a small sampling of the vast body of knowledge that exists about countering DDoS attacks and keeping a popular website online. If you would like to explore this topic further, I have included links below to help you get started.

- Etsy’s Code as Craft

- Network Security Through Data Analysis by Michael Collins

- Building Microservices by Sam Newman

- High Scalability Blog

- Weathering the Unexpected on ACM Queue

- Distributed Systems for Fun and Profit by Mikito Takada